Curating Pacific Spaces: Oceania and the White Cube

A visual presentation delivered at the 3rd Contemporary Pacific Arts Festival Symposium at Footscray Community Arts Centre, Melbourne, Australia (9-11 April 2015).

Curating Pacific Spaces: Oceania and the White Cube

Ema Tavola

I want to acknowledge this ancient land, the wounds of colonisation and the resilience of its people. To the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, from my ancestors to yours, I come with love and deep respect.

I’d like to thank the organisers of the Symposium and the Festival as a whole. There are different ways to measure success in the creative industries and my position on centralising Pacific audiences within my practice as a curator, has often attracted criticism. With every challenge I’ve encountered, my beliefs and values galvanise; I know the work that I’m doing is my purpose.

My knowledge is from experience, not books and academia; my projects are peer reviewed by my community. Thank you to the organisers of this Symposium for giving visibility to my practice, and acknowledging alternative pathways in the development of the thinking, presenting and making of contemporary Pacific art.

To take it back to the language old school, curating is about caring, and I care about Pacific art, Pacific people and Pacific spaces. I care also that Pacific is not a word that reflects the mana, potential and prowess of this extraordinary region, but from my monolingual perspective, I use English words and hope to contribute to the expansion of their definitions in describing a peoples and our creative expression.

I use Oceania here, because there’s nothing peaceful, tranquil or passive about my practice. And I speak from the position of living in diaspora, in Aotearoa New Zealand as a mixed race Fijian woman.

The White Cube, or the ‘gallery’, is a form of sanctuary for me. It is a safe space for mixedness, for dialogue… a space for silence, where language can be unspoken. It can be an empowering space, an emotional space. It’s where art defines its community.

I started trying to bring the two together, Oceania and the White Cube, when I was an art student. I spent my days learning about concepts, frameworks and aesthetics from the West, and experimented with applying them to visual codes and experiences from my life and identity. Like many Pacific artists, I was starting to create work from the space between two worlds, but ultimately to make art within the Eurocentric cultural paradigm of art school, one world dominated the other.

I was working with themes relevant to my community, but my community wasn’t critiquing my work. In the opportunities I had to bring my people and my art together, I felt diminished for the lack of value that was assigned to my new art language. I felt lonely… and confused because my art school was in the Polynesian dominated South Auckland suburb of Otara.

Art school taught me about power and ways of seeing. Assisting visiting resident artists at Manukau School of Visual Arts[1], Amy Plant (UK), Alwin Reamillo (Phillipines) and Juan Castillo (Chile), opened my eyes and my heart to the idea of working outside of the context of art school, in real spaces with real people. Ironically, it was these international artists and their socially engaged practices that became the catalyst for my ongoing relationship with Otara and South Auckland, the place I’ve lived for the past 13 years.

I came out of art school with a firm desire to side-step the art world; I had a growing understanding of the dynamics of my relationship with the space around me; the cultural, social and political landscape. My art practice evolved into a curatorial practice, still concerned with space and form, beauty, history, aesthetics and impact. And a pathway to public service enabled me to hone my skills in curating, event design and delivery, advocacy and governance.

I worked for over six years as a public servant in the role of Pacific Arts Coordinator for Manukau City Council (later Auckland Council)[2]. Within that capacity, I was able to instigate the establishment of an exhibitions gallery dedicated to Pacific art and artists called Fresh Gallery Otara. Over this time, my practice as a curator became my job and empowering and supporting the development of Pacific artists, and Pacific audiences, became my core business. As a council officer managing public resources, the region’s ratepayers and local communities were the audience of accountability.

Fresh Gallery Otara’s programming was site-specific and targeted; it responded to the community’s unique demographic and served as an important professional exhibitions space for the local art school. Otara is one of Auckland’s densest Polynesian suburbs. Situated 20km away from the Auckland CBD, it has a population that is approximately 70% Polynesian and 20% Māori, and around 40% of the population is under 21.

Over six years of curating for Fresh Gallery Otara led me to draw some fairly well evidenced conclusions about what works, where value and values lie with Pacific audiences, and the ways in which exhibitions and curating can contribute to social development by empowering communities through dialogue, awareness-raising and creativity.

Working with public money and the accountabilities of public service taught me that understanding the values, beliefs and lived realities of your customer / audience embeds meaning and mana in your work. From my experience, curatorial projects that created impact and affected peoples’ hearts and minds, generally touched on one or all of these ideas:

- When lives and experiences are reflected, shared and affirmed

- When familiarity enables visual language to be read and interpreted

- When art stimulates discussion about issues that affect our lives

- When art speaks to the spaces between us, the tangible and intangible things that heal and formalise relationships

- Where a human interaction in between art and audience enables informed engagement

So, I’d like to introduce a few projects, artists and events that have Pacific people at their core.

Social stigma and misconceptions about South Auckland as a place full of Polynesians, ethnic minorities, deprivation, crime and violence[3], are well embedded in New Zealand society. The struggle is real: an environment affected by well-defined systemic inequalities is the reality for a lot of people. Perhaps as a result of adversity and survival, culture and community, faith and family make up vital social infrastructure. A lot of people work really hard to ensure young people in South Auckland aren’t limited and negatively affected by the environment around them.

One of the most powerful platforms for this is an event established to give the region’s young people centre stage, and celebrate the transmission of cultural knowledge. Now held over four days, schools from around Auckland and even as far as Niue, compete in cultural performance and speech making for massive audiences. The annual Māori and Polynesian secondary schools cultural festival, aka Polyfest, celebrated its 40th anniversary this year and it is one of the most empowering spaces I’ve ever encountered, and a true product of South Auckland.

I started attending Polyfest as a spectator and loved the energy surrounding not only the performers, but the audience; it is a place to be seen, where clothing, hair, identity and culture are on display in full force. Every year, thousands of photos are made at Polyfest, but largely focus on performers and smiling groups of posing young people. An exhibition developed to mark Fresh Gallery Otara’s third anniversary in 2009 was an opportunity to honour Polyfest and the style confidence of its audiences. The first of three Polyfest Portrait Projects was born to also address the relative invisibility of empowered images of young Pacific people in our everyday lives.

I wanted to capture the nuances of South Auckland’s worn identities from Tongan ta’ovala and Samoan ‘ulafala improvised from $2 store materials, to the home-made Puma stencil lavalava. Polyfest-goers and their personal style are expressions of self and community, embedded in global and local influences.

I worked with Fiji-born photographer, Vinesh Kumaran, to set-up a make-shift photo studio and we hand-picked around 60 stand-out subjects whose style stuck out from the crowd. Vinesh relocated with his family from Fiji to South Auckland as a child after the 1987 coup; he has grown up in the suburb of Māngere, studied photography at the local art school and gone on to have a successful commercial practice. His heart is in portraiture and he treats a photograph as a collaboration; a moment of connection captured between him and his subject. He understands the power and politics of the lens and the position of the photographer.

From this first Polyfest Portrait Project, we planned to select eight photographs to print life-size; four male and four female. The photographs were exhibited alongside collections by two local artist designers who were inspired by South Auckland youth / street / hood style. Ofa Mafi, who made screenprinted customisations of readymade garments from Op Shops and Chinese stores in Otara, and Allen Vili, who made one-off airbrushed paintings on readymade white hoodies. A free poster featured all the portraits made at Polyfest that year, and Francis Falaniko became the poster boy for the exhibition.

We re-staged the project in 2012 with a new focus on hair. Vinesh and I were particularly inspired by a series of ethnographic photographs which have been used widely by the Fiji Museum documenting Fijian hair styles. The idea of creating a kind of new photographic hair archive of South Auckland was appealing and slightly ethno-dubious, so we went down a fairly cliché pathway with the woven mat background.

We shot 66 subjects on this day. The photographs featured in Fresh Gallery Otara’s 66th exhibition, marking the Gallery’s sixth anniversary, and my last exhibition before leaving the role.

We were struck with the artisty of cornrows, the idea of hair design being viewed from all angles, and the attitude that goes with good hair!

The photographs were displayed in an install inspired by popular photo sharing app, Instagram, in front of a vintage barber chair borrowed from New Flava Barbers, a Tongan-owned barbershop down the road from the Gallery. As part of the exhibition’s public programme, Tongan barber, Allen Tonkin came in on Saturdays to do free art haircuts for the duration of the exhibition. On willing subjects, Allen enjoyed the opportunity to flex his Polynesian pattern skills surrounded by eager observers. I’m intrigued with the culture around barber shops and loved the opportunity to bring it into the Gallery. Mostly though, I enjoyed that a fresh haircut, made a young boys feel good in their skin, confident and pretty skux.

This exhibition was called WWJD (What Would Jim Do?), it honoured the legacy and influence of the late Cook Islands curator, Jim Vivieaere. As my last show at Fresh Gallery Otara, I pulled together an eclectic mix of my most favourite artists, friends and collaborators. In the exhibition’s diverse offerings, the connections and juxtapositions, invited audiences to unpack the works and their themes, creating conversations and pretty robust curatorial analysis!

Sangeeta Singh’s painting, “i have fish eyes, shark teeth and i chase dream tails” inspired readings and interpretations from a wide ranging audience.

Sangeeta’s paintings seem to represent a visual language that people can interpret because they connect with her vulnerability. The readings of silence and struggle, power and powerlessness, strength and darkness bring out views and responses that speak to shared human experience.

Part of me feels protective of Sangeeta’s work, perhaps for the embedded triggers that linger in the space between her paintings and the viewer. But I think she’s making some of the most important work about Fiji and Fiji Islander experience and I’m one of her biggest fangirls.

The presentation and politics of female nudity underpinned another important exhibition at Fresh Gallery Otara, Ngā Hau E Whā – The Four Winds, a solo exhibition by local artist Leilani Kake for the 2011 Auckland Arts Festival. Leilani wanted to confront body politics and self-image as a response to high and disproportionate rates of Māori and Pacific Island women dying from cervical and breast cancers in Aotearoa New Zealand.

In her most ambitious work to date, this four-channel video installation presented life-size projections in a blacked out room of naked women floating in and out of watery darkness. The subjects were four women from the Cook Islands, Papua New Guinea, Samoa and Tonga. They were in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s, three mothers, one grandmother, one pregnant, each from different walks of life. They maintain eye contact with the lens, confronting the viewer, and fade in and out of view. This work challenged taboos head-on and required careful negotiation of relationships and access in the context of South Auckland’s highly conservative faith-based community.

The responses to this work surprised us all. We shared tears on an almost daily basis with people sharing stories of mothers, aunties, sisters and grandmothers who suffered through breast and cervical cancers. And overheard teenage girls giggling and critiquing the bodies in harsh and unforgiving language perhaps indicative of the unrealistic body expectations they encounter in mainstream media that shape their own worldviews.

From young men, we listened to the ways in which the work made them feel respect and gratitude towards the women in their lives. That the different body types and different ages showed that a body is a body. The artist’s message and hope that the work would inspire women to confront their own body taboos and get checked to avoid preventable suffering, was interpreted and discussed confidently by a lot of our young male audiences.

Leilani makes works notoriously hard to photograph; they are very much about the moment between the viewer and the work. Whilst every other work she has made and presented at Fresh Gallery Otara has gone on to be shown at other Galleries, this work has yet to be re-shown.

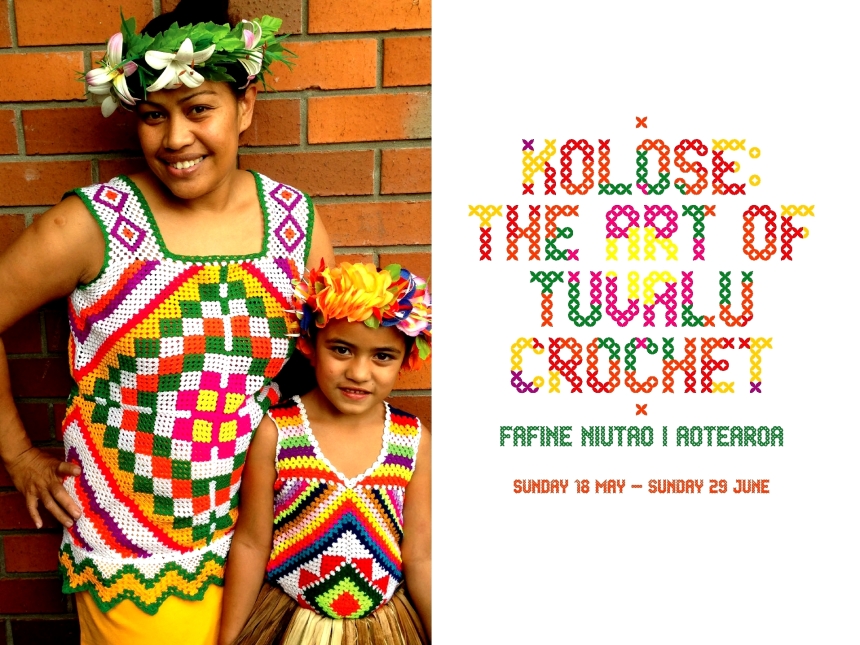

A Pacific art exhibition I consider to be ‘curating Pacific art best practice’ took place last year in South Auckland. Kolose: The Art of Tuvalu Crochet featured works by the Tuvaluan arts collective, Fafine Niutao i Aotearoa; the exhibition was curated by Tongan curator Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai and Tuvaluan journalist, Marama Papau.

For as long as I’ve known Kolokesa, she has fought hard for ‘heritage artists’ to be considered as contemporary artists. In her efforts, she has challenged academics and institutions, curators and marketing people to unpack preconceived notions of ‘traditional’ arts. The argument is that ‘traditional’ practices have evolved and adapted, and practitioners demonstrate as much innovation and knowledge of their respective ‘art histories’ as contemporary artists, particularly those who have graduated from art schools.

In our shared responsibilities as Associate Curators for Auckland Art Gallery’s problematic Pacific survey exhibition, Home AKL (2012), I witnessed Kolokesa’s staunch advocacy for the rights of heritage artists with contemporary practices, particularly in relation to the institutionalised financial value scale.

Kolokesa is a traditional Museum curator; she doesn’t blog and tweet her angst, like me (lol), she writes hard hitting academic papers, travels to conferences all over the world, confronts and critiques academic authorities on Pacific art, respectfully reminding them that Pacific people are the authorities on Pacific things. She also actions her perspective in the form of powerful exhibitions that ensure heritage artists and their contemporary practices are acknowledged, understood and contextualised as vital cultural producers and knowledge powerhouses fully integrated into contemporary life in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The image I used as the first slide of this presentation (above) exemplifies the notion of shifting the centre and the margins towards a different way of considering Pacific people and art in the ‘White cube’. This photo is from the exhibition’s opening at Mangere Arts Centre – Ngā Tohu o Uenuku, another Council run gallery in South Auckland.

The Council representatives sat on the periphery, the Tuvalu community filled the room with the elders at the centre. The cultural performance at a Pacific art exhibition opening has become a cliché, but here, the buffer of the mamas and papas between the formal guests demonstrated the wholeness of the community, and that Pacific art and creativity is inextricable from Pacific people.

The exhibition featured quilts, pillow cases, wall hangings, crochet tops and skirts as well as performance garb. I loved the installation of the tops hung at adult height; they subtly created a mass presence of their wearers even without them there.

The women artists were brought together with free transport and appropriate hosting; their needs were cared for and their Tuvaluan liaison in the form of co-curator, Marama Papau, ensured the experience was intergenerationally empowering and valuable.

One of the exciting outcomes for the exhibition was the definition of ‘Contemporary’ being assigned to the artists in Fafine Niutao I Aotearoa. Where terms such as ‘heritage’ or ‘traditional’ artist might normally be used, the curators influenced the use of the term ‘Contemporary’ as a formal title that was used on the story produced for Tagata Pasifika on TVNZ.

Since leaving the role of curating for Fresh Gallery Otara, I’ve been teaching a year two degree level paper called, Pacific Art Histories: An Eccentric View at Manukau Institute of Technology Faculty of Creative Arts. In a sense, it’s a full circle – I took this paper in 2003 when it was taught by noted Niuean poet and painter, John Pule. The paper itself was originally written by Jim Vivieaere and Albert Refiti in 2001. To have been given the opportunity to rehash the paper from scratch, and to teach in general, is a privilege.

My students get a semester-long crash course in Pacific art issues, tensions and aesthetics; it is less about the past, and more about what is happening today that will shape the future. The student body at the Faculty is majority Polynesian and Māori and local to South Auckland.

They’re spoiled learning about contemporary Pacific arts practice in Auckland; they have Fresh Gallery Otara down the road and new Pacific art exhibitions virtually every month around the region. In a class averaging about 20 students, floor talks and studio visits enable intimate insights into Pacific art practices that come from Auckland spaces and experiences, for Auckland audiences.

I enjoy lots of things about teaching, but I really enjoy encouraging my students to think critically about context, audience and value systems. After visiting New Zealand artist, Robyn White’s exhibition Ko e Hala Hangatonu: The Straight Path (2013), they wrote at length about the nature of the collaboration between White and the indigenous barkcloth makers, about intellectual property and the cultural skills, knowledge and meaning that felt marginalised in the presentation of White’s finished work in a dealer gallery in central Auckland.

Earlier this year I curated an exhibition that challenged me to think beyond South Auckland and the ease of engaging with readymade Pacific audiences. Between Wind and Water for Wellington’s Enjoy Public Art Gallery was an experimental repositioning of the ideas that underpin my practice. Tanu Gago, Leilani Kake and Luisa Tora each made new work for the show and travelled to Wellington for a two week residency where we collectively hosted art talks, panel discussions and gathered daily to meet people, break bread and represent South Auckland in the capital.

Leilani Kake’s work was entitled, MALE – Māori or Polynesian. It is a lenticular print combining three portraits of relatives and responds to her recent research into narratives of cultural identity and incarceration, stereotypes of criminality and the dichotomies of criminal/victim, brother/other. In efforts to engage new audiences, the artists were invited to consider ways to foster dialogue around their themes, and Leilani made a series of IdentiKit booklets inviting viewers to create customised drawings from eyes, noses and mouths of Pacific and Māori sports and entertainment stars.

In what was quite a relaxing activity, ideas and attitudes towards the themes of Leilani’s work started to be revealed at ease. In the case where we were present to have a conversation, the work started to create its audience and define its relational space; people talked about stereotypes and statistics, about being targeted and experiences with the Police, about fear and misunderstandings.

Between Wind and Water was a new territory for me but demonstrated the value of Pacific art that is made in an empowered space, that even without its people, it still carries their presence and politics.

The publication for Between Wind and Water is available to read online. It’s a record of an epic undertaking including three artists, six events, two protests and hundreds of kilometres driven every day with a grizzly baby. It features written and drawn contributions by Fuimaono Karl Pulotu Endemann, Tanu Gago, Jessica Hansell aka Coco Solid, Leilani Kake, Kaliopate Tavola, Dr Teresia Teaiwa, Luisa Tora and Faith Wilson. It was kind of an epic dream project.

I’d like the last word to be from Jim Vivieaere, a mentor and inspiration. I had the opportunity to host a gathering in 2010 for Pacific curators and Jim spoke. He was the most eloquent, courageous Pacific arts thinker. Never pinned to an institution for long, he created wide reaching networks who all mourned his passing in 2011.

Jim empowered me to use the language of curating as my voice.

My travel here from Aotearoa has been made possible with a grant from Creative New Zealand, our national arts investment agency, and for that I am deeply grateful.

My engagement with Melbourne started with an artist whose practice, research, and commitment to Fiji and the Pacific, has always inspired me – Torika Bolatagici, thank you for everything.

Thank you for listening.

Vinaka vakalevu.

References

Baker, C. Good intentions: A case study of social inclusion and its evaluation in local public art galleries. Unpublished master’s dissertation for master’s degree, Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved March 27, 2015, from http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/3728?show=full

Māhina- Tuai, K., Papau, M. (2014). Kolose: The Art of Tuvalu Crochet (Lopiani and Violeta Papau, Trans.) (1st ed.). Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland Council.

Māhina- Tuai, K. (2012). Matala Festival 2012: Review. SOUTH, 2, 12-17.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Winnipeg, Canada: Fernwood Publishing.

[1] Manukau School of Visual Arts is now the Faculty of Creative Arts, part of Manukau Institute of Technology.

[2] The Auckland region’s seven territorial authorities were merged into a ‘Super city’ singular model in 2010; Manukau City Council was the local authority from 1989-2010 of the area commonly referred to as ‘South Auckland’.

[3] Ringer, B. (November 28, 2008). Give South Auckland a little respect. NZ Herald, Retrieved from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/opinion/news/article.cfm?c_id=466&objectid=10545407&pnum=0

Leave a comment